THOMAS GRAEME CAMERON GIBSON

A CELEBRATION

Bagpipes: Kevin Barry

Welcome and introduction: David Young

Friend since early 1970s, co-conspirator in such ventures as the Writers’ Union,

the Eclectic Typewriter Review, and the Writers’ Trust.

Eugene Benson reading from Five Legs

Playwright and author Gene was the first person to read Graeme’s work, in the 1960s. He took him to task severely, and Graeme said that’s what made him a decent writer.

Louise Dennys: Graeme’s books, PEN, and Graeme as a writers’ advocate

Louise is from PenguinRandom, one of Graeme’s publishers, but is also a family

friend and was mentored by Graeme for her role in PEN

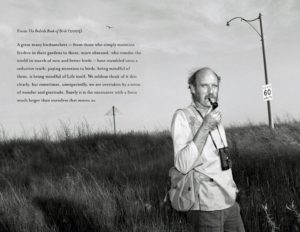

Harold Atwood reading from The Bedside Book of Birds

Dr. Harold, neuroscientist, was Graeme’s brother-in-law and also a long-time

conservationist and birdwatcher.

Ian Davidson: Graeme as a birdwatcher and conservationist

Ian has been with BirdLife International, with Nature Canada, and with the U.S.

Fish and Wildlife Service. He and Graeme collaborated on a number of projects.

Kith and Kin: Ivy Mairi, Martha Farquhar-McDonnell, and Kathleen McDonnell: sing “Thousands or More” (traditional) and “Cool of the Day” (Jean Ritchie):

Rick Salutin: Graeme’s life as a human being

Rick is an old-time friend and fellow writer; in the past year he and Graeme

had many retrospective talks.

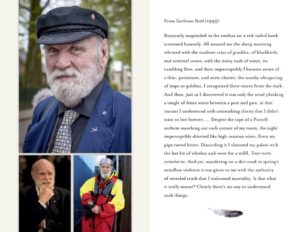

Jessica Gibson reading from Gentleman Death

Jessica is Graeme’s niece, daughter of his beloved brother Allan

A toast to Graeme, led by Carlyn Moulton

Art Gallery owner Carlyn has been a friend since 1976, when she first arrived at the farm straight from Bible school to help with the sheep and Margaret’s fan mail.

Jamie Snyder sings “The Parting Glass”

Closing fiddle music by Jamie Snyder.

ABOUT GRAEME

Graeme Gibson summoned something in all of us. We entered his force field to warm our hands on the fires of his convictions. We enter that same force field tonight as we come together to remember this remarkable man we loved so dearly…this man who changed us.

Since Graeme’s passing I’ve been thinking a lot about our early days together. About the person I was when I first met him 46 years ago…and how he changed me. As I tell you a couple of my Graeme stories I want you to summon your own private Graeme Gibson. And I want you to remember the person you became in his presence. That version of yourself that he magically summoned when he cast his conversational spell. We will use your memories in a moment, to amazing effect. A vivid hologram of Graeme Gibson will hover above us in this room.

Count on it.

But first, to get this memorial service off on the right foot I’d like to do a pretty darn good mime impression of Graeme Gibson.

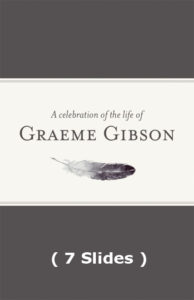

This is Graeme lighting his pipe on the day I met him 46 years ago. Imagine that I’m wearing a ragged blue denim shirt and a little kerchief. This is my pipe. And this is a wooden match. (mimed action)

The magic of mime. It’s almost like being there.

So, here’s my first story. It’s the late 70s and Graeme and I are birdwatching in Cuba with his friend Garedo who was the greatest ornithologist and field naturalist in Cuba until the revolution came along and changed everything and he was suddenly reassigned to be a tennis pro at the Hemingway yacht club and spa. Graeme had a soft spot for quixotic folk like Garedo. He felt a kinship with them because he understood in his bones what it meant to be an outsider.

So there we are tramping through the Cuban bush for a few hours. Garedo is taking us to the secret location of a Grundlach’s Hawk nest. This raptor, an endemic in Cuba, was an endangered species. There were only a handful of breeding pairs left so this was a very special outing. As we tramp through the bush Graeme and I compare notes about the previous evening when we’d drunk and talked and laughed at a reception at the Dutch ambassador’s residence in Havana. Despite his outsider status Graeme knew how to engage with fancy people. He was a man of urgent enthusiasms. He had an infallible ear for the issues of the day. A silver tongue for reasoned debate about lofty ideas. AND he understood the way great policy could curve time and space and shine a bright light on a better future. In fact, in another life Graeme would have been a terrific Canadian ambassador.

Imagine it now. Graeme and Margaret on a five-year posting in Bulgaria. Margaret writes her iconic Iron Curtain Trilogy. I can see it.

Anyway, after hours of bushwhacking Garedo hushes us as we arrive at the base of a tall tree. Way up there, an enormous nest of woven branches. Now, I’m not a serious birdwatcher. I’m here because I want to hang out with Graeme. Nonetheless I know this is a very big deal. A Grundlach’s Hawk is extremely rare, a nesting pair even more so. And we’re looking up at that nest through our binos…and a fledgling appears and leans over the edge…to look down upon us.

A fluffy baby hawk, soft as a plush toy, eye like a gold dubloon, looking straight down at us. The fragile future of this endangered species is right there.

Suddenly Graeme has this grave look about him. He whispers: ‘Okay, that’s enough, let’s go. We shouldn’t even be here.’

And so we left and tramped back through the bush for two hours.

That’s my first story.

My second story is about Kipawa. I was maybe 30 and going to Margaret Atwood’s ancestral camp in the Quebec bush for a few days was a very big deal for me. Wanting to make a good impression I think I brought forty bottles of wine. Graeme had promised me that we would go out one day at dusk and catch a pickerel. Now, Graeme was a lot of things but I don’t think he was a serious fisherman. Nonetheless, he had that conviction about him, that fisherman gravitas, so I bought in. We would fish from the canoe at the base of a steep rock face. He had heard that pickerel schooled there in the cool, deep water. We didn’t have a landing net so Graeme got a bushel basket and laid a bed of sphagnum moss in the bottom of it. I knew he was bullshitting me (and probably himself) with these olden days fishing techniques but, as usual, I was in his thrall. Pickerel fishing, olden days style. Let’s do this!

Graeme lowered a spinner over the side and started to lazily jig it up and down. The water around us so still and crimson red in the magic hour. We passed a flask back and forth and quietly shot the shit. Probably talking about our fathers. No way were we going to catch a pickerel…but we were having a wonderful, quiet conversation…which was, afterall, the whole point of it.

I felt so lucky to know this man who would talk to me in a quiet deep way about the things that really mattered…and actually care about what I had to say. He was that special big brother…the one who listened. Graeme showed me a new conversational wave length. An expansive way of talking that invited the big ideas in.

In so doing he made me see myself in a new way. That is what I loved most about this man. The way he made me see myself.

BAM! His rod bends double and the line races away and we are so shocked that we almost dump the bloody canoe! This is obviously a huge fish! And Graeme is way-way out of his skill set and he’s playing the fish on his spinning tackle and telling me to get the bushel basket full of moss over the side – so I do that and the water is still and clear and here comes the pickerel circling up toward us from the depths – it’s this big! – and I position the bushel basket underwater and the massive fish magically swims into it and I haul this monster into the centre of the canoe and it OBLITERATES that bushel basket with its mighty thrashing tail! Smashes it to smithereens! Moss everywhere! And Graeme is suddenly there with his buck knife and he jabs the fish once at the base of the skull…and stills it…and there we are in the sunset waters of Lake Kipawa grinning like fools, both a bit drunk….too stunned to say anything.

We paddled back to shore in the blue hour, refining our story as we went. Who had thought what when we were paddling out to the secret fishing hole. Our very low expectations about actually catching anything. The ridiculous bushel-basket-with-moss concept. And then this miracle fish…this technicolor movie – everything in slow-motion as we went back and forth over the details of our adventure, shading the highlights this way and that…and just enjoying the hell out of it.

By the time we reached shore we were both in genuine boyhood again, sharing a youthful comradery we had somehow missed when we were growing up.

Peggy was there as we pulled the canoe in, ready to hear the stories and take the piss out of us.

We cleaned that pickerel and we ate it for days…and we drank forty bottles of wine.

Those are my two memories.

Now it’s your turn to remember.

We’re going to do a tiny nano-meditation together to summon that Graeme Gibson hologram with our collective mental energy.

Please, take this seriously, I want you to close your eyes now and keep them closed…

I want you to think of Graeme that day you really loved him.

That day he understood you.

That day he helped you.

That day he listened to your problems and was so funny and kind.

Summon the best of him…the way he summoned the best in you.

Now…bring his energy field, the very essence of who he was, to a single point of focus in your mind.

And now…let that energy fountain up out of your crown chakra and form a shimmering Graeme Gibson hologram above your head.

In your mind’s eye see him floating there…his pure light.

And now you can open your eyes.

Well done.

We are ready for big fun.

Because Graeme is here now.

You brought him with you.

GRAEME AS A FORCE IN OUR PLACE AND TIME

AS A WRITER AND WRITERS’ ADVOCATE

Graeme is so beloved to all of us here…. But his influence as an extraordinary cultural force goes far beyond this room. His passions and energy, his unique abilities transformed Canada’s cultural life, indeed our sense of freedom and possibility. He was a giant among us. Which has nothing to do with his estimable height…but all to do with his character, with the trust he engendered, with his quality of leadership. Like a lion passing by, he left his imprint on this ground, on our community and our country.

I had read his books before I met him in the late eighties, and I was already smitten. In the early 70s, an activist writer and novelist of 32, Graeme had recognized the need and hunger to build a coherent community for writers — for none existed. One thing he did was to record the first ever book of interviews with Canadian writers –from Alice Munro to Timothy Findley…and Margaret. That labour of love, simply titled, Eleven Canadian Novelists Interviewed by Graeme Gibson, is a prescient record from a wild and exciting literary time. He took all the author photos too: young Mordecai Richler and Margaret Laurence, cigarettes dangling; a sweet, thoughtful Matt Cohen…. In his Introduction he lauds the avant-garde small presses from Anansi to New Press, who were springing up to publish his friends and fellow writers–Anansi alone put out a good third of all the fiction published in Canada, though it was far from a household name. He recalls how the woman hired by the CBC to transcribe the interview tapes turned out to be hard of hearing, and relentlessly, albeit innocently, translated “the House of Anansi” into “the House of Nazis” through the entire text.

And then the novels: I remember to this day where I was when I reached that moment in Graeme’s novel Perpetual Motion when the soon-to-be-extinct Passenger Pigeons, streaming in over the forest in clouds of tens of thousands that darken the mid-day sky, descend in a violent storm of blue and green sound-and-feathers to ravage the crops. And the farmer lifts his gun…. Graeme holds us there in the beauty of it, in the brutal reality of survival, and in the sorrow of extinction, and I fell in reader-love with the writer, as we do with all great books, and with the intricate mind that could imagine so democratically, in such fierce, precise language, the complex tensions of a changing world. He observed that world with a truthful obsessive attention.

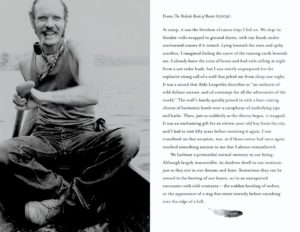

The same attention and love he brought back again a dozen years later to his spectacular marriage of text and images in the internationally acclaimed The Bedside Book of Beasts and its great forerunner The Bedside Book of Birds in which he traces writings on birds from Aeschylus to Murukami. “But,” one reviewer wrote, “the very best writing in the book belongs to Graeme Gibson himself, both in the beauty of the writing and the ideas contained therein.” And little could be more true of its author than this: “It is a book, most especially, for those who wish to accompany a noble mind into the heart of things.”

Then, after four impressive novels, he forthrightly declared “I don’t want to start chewing my cabbage all over again.” He had other hard work to do. Though he modestly said “I know I’m not going to change the world,” just consider this: he had a founding leadership role in the Writers Union, the Writers Trust, the Book and Periodical Council, PEN Canada, and more, and along with friends in this room, Margaret, Eugene, David Young included, he set out to safeguard the small but determined community of Canadian writers so that it might flourish. He gave strength to a newborn literature and to Canadian ideas and in so doing did change our country. A legacy for which every one of us—just as plain citizens– must be grateful.

And then came the formation of PEN Canada, arguably today one of the strongest, most effective PEN country-Centers in the world. Early on he had described himself as not being competitive with other writers—that he just didn’t see the world in those terms. Now he said: “we were ready, on some level, to have a less selfish interest. For the first time we were not working to create an organization that would benefit us, would protect us, the writing community in Canada. You are there at PEN to do stuff for someone else.”

I first met him at the big wooden table in the PEN Canada office—courteously batting away the clouds of tobacco smoke from his pipe, which drifted around him. It was 1988, I was a green new board member and he was heading into his last year as president. Watching him in action as head of that fledgling organization, which had begun around his and Margaret’s dining room table on Sullivan Street just five years earlier, one could only marvel at his innate quality of leadership: he commanded a room, he took on what seemed impossible dreams…and people followed him. After the war, Graeme–following his own much decorated father Brigadier-General Gibson–had briefly become a soldier before going his own independent way. His astonishing ability to organize collectively—from the Writers Union to PEN –he attributed in part to his military training. As Jess said astutely, he knew what it was to be the subordinate as well as the leader. Also, he was REALLY good at diplomacy. He communicated a kind of forthright gravitas.

And when the “Rushdie Affair” jolted us into a different world, Graeme’s response to it was magnificent. I watched with awe. As the old, dying Ayatollah Khomeini, in an attempt to pull the drifting balance of power in the country back to him, issued his infamous fatwa, the chorus of condemnation of the book and of Islam was loud —and included many liberal thinkers, indeed even many writers. It was a genuinely frightening time: a publisher was shot; two translators killed; here in Canada the publisher received death threats, and bookstores began to receive bomb threats, windows were broken. And Graeme went into action. When no one else would say BOO (to quote Margaret), he made himself the public point man. He called up the senior mullahs in Toronto and in Montreal, and set off to meet with them in both cities. He went alone. He set out to listen, yet to make his case at the same time against a global call for assassination, to diffuse the situation with calm discussion; he went on television with the senior leaders so they could all express their views openly, together. And, with courage and unassailable integrity, he said I’m listening to you, I hear all you’re saying. But…that isn’t how we do things here.

I know that what he did helped ensure that no serious damage or repercussions occurred anywhere in this country. He stepped into the complexity of the moment personally and into the heightened divided emotions with his own thoughtful, determined intelligence to ensure the safety of all and, beyond that, ensure our cities would not devolve into the book burning and attacks witnessed in other countries across the world. He looked at all sides—one of his phrases that I loved was his often reiterated “but then again”. “We’re all going to die” he once said, “but, then again, we should live as if we could make a difference.” He held dear the idea that if you live in a community you have responsibilities; that you don’t get the benefits without the responsibility; that so-called freedom—freedom of expression—is earned. In his own self, he showed how a duty of leadership is a duty to be present. To be present in the world. And with that comes a duty to listen. Which requires as much courage as the responsibility to speak out.

A last sweet story about Graeme. John Ralston Saul told me about a famous fundraising meeting that Graeme and he had in ‘89 to seek financial contributions towards the important first International PEN Congress to be held in Toronto and Montreal. It was, and is to this day, considered the most breathtaking Congress held in any country, and ended up being the single biggest gathering in Canada of major world writers—among them, Chinua Achebe, Harold Pinter, Arthur Miller, Betty Friedan et al. Putting that cross-country Congress together was one of Graeme’s greatest contributions to establishing not only PEN but this country as a literary center, demonstrating the reach and power of Canadian creativity and writing. So the two met cordially with one of this country’s wealthiest (very wealthy) industry captains, who was publicly an outspoken supporter of Canada playing a cultural role in the wider world, to ask if he would therefore be generous enough to put up some money towards the costs of this first ever world gathering here – and they returned home feeling pretty pleased with themselves that they’d been successful. Then the cheque arrived a few days later— for $995.00… not even a thousand. The organization could probably have used even that, but Graeme’s integrity and gutsy pride were, as always, unassailable. As was his humour. He put the cheque back in the envelope and returned it with a courteous note: ‘Thank you, but given the amount of the contribution it strikes us you must need the money more than we do, so we are glad to return it to you.”

Graeme was a friend to our aspirations and ambitions, our country, our place and time. He did make a difference. He did change our world. He lived with moral imagination. As Margaret and the family said so well: “We”—in this case I think “we” is also all of us gathered here—“are grateful for his wise, ethical and committed life.”

And, elegant and gently kind as always, when he stopped being able to read books he said to me reassuringly, as we sat out in the garden this last summer, “That’s ok—I read the world around me.”

CELEBRATING THE NATURE IN GRAEME

Many of you knew Graeme’s celebrated written words; I knew Graeme through his passion for nature. Our travels together took us to places near and far, and through our journeys together I was privileged to get to know a man whose patience, optimism, insight and sense of social justice changed my world view and filled me with hope that each of us can contribute towards making this a better world – for birds, beasts and, of course, people.

I remember meeting Graeme for the first time in Greenland. The chance arose when a spot became free on a late summer Adventure Canada arctic cruise and I was invited to join Graeme, Margaret and friends of BirdLife International to “bird-watch” and raise awareness of bird conservation issues – who could say no? A boat is a finite space and lends itself to meeting people and building new friendships. I instantly took a liking to Graeme; he was a giant of a man, warm to the core, with a great sense of humour and a twinkle in his eye.

A year later I joined Graeme again in Buenos Aires at a gathering of BirdLife’s partners from around the world to discuss the fate of the world’s birds. At the time, Graeme and Margaret were co-presidents of BirdLife’s Rare Bird Club. After a small cocktail event at the Canadian Embassy, I noticed a familiar face peering from the elevator. It was, of course, Graeme with his Cheshire cat grin, and I responded to Margaret’s finger motioning me to join them – and we escaped from the hordes and continued conversations that we had started in the Arctic but had never finished. Such was our relationship – long stretches of distance interspersed with wonderful, engaging and conservation-filled discussions.

Graeme was grounded in a sense of place and nowhere was this more evident than Pelee Island. It was here, with his son Graeme the Younger and his partner Sumiko, that he helped establish the Pelee Island Bird Observatory (PIBO) – a local organization devoted to the study and conservation of wild birds and their habitats. PIBO’s work is helping to shine light on the island’s role as a critical stepping-stone and conduit for millions of North America’s migratory birds. So passionate was he about the islands that together with Margaret, they organized “Spring Song”, a week-long event featuring celebratory writers and raising awareness of the island’s globally Important Bird Area designation and the need for its preservation.

Graeme’s engagement with Canada’s conservation community was legendary – starting with his role as a board member of the World Wildlife Fund, contributor to the Nature Conservancy of Canada, advisor to Nature Canada and Birds Canada, supporter of the Wildlife Conservation Society and Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society’s work in the north, to name but a few. He was also a vocal environmental advocate and never shied away from the media. I recall a major gala event at a renowned downtown Toronto hotel where Graeme and Margaret brought their dinner in a lunch box to protest the hotel’s construction of a luxury development in the last remnant forest of the endangered Grenada Dove (of which there are probably only a handful remaining). Although the hotel was eventually built, Graeme’s protest encouraged the protection of the species’ only known habitat.

Graeme’s attention was taken by the inextricable link between nature and human well-being. If you were with Graeme long enough, you would have heard him comment about the importance of forest bathing or shinrin-yoku; a term that describes the Japanese practice of being in nature and letting its therapeutic powers ease our stress and worry, help us relax and think more clearly. Graeme was a passionate advocate of forest bathing and bird-watching provided the perfect excuse (if any was needed) to combine the two. Indeed, Graeme might have claimed that to bird-watch was to bathe in nature.

And from all of this, Graeme taught me the importance of being present to bare-witness to events shaping the natural world. Graeme was an agent for positive change – and change events he did – not only by the acts I have described but indeed by the way he chose to live his life with his family, friends and colleagues. And while I truly miss a great friend and mentor, I celebrate his life today and take forward gifted memories of our times together.

In closing tonight, I leave you with a poem sent by my friend Dr. Andres Bosso, a passionate ornithologist and renowned Argentine poet. We both met Graeme at the BirdLife event in Buenos Aires and Andres was touched by the essays in Graeme’s The Bedside Book of Birds, which he read subsequently. Andres contacted me last week and asked if I would read aloud today a poem he wrote about the Burrowing Owl (“Buho”) in dedication to Graeme’s fascination for grasslands and their birds. Translated, it reads as follows:

The pampa complains through its birds

And the great complaint of the field ends in a post

A hard and wired post

Curiously opposed to this complaint of feathers, soft and free

A wise complaint, a presence that hypnotizes.

Go softly Graeme.

Ian J Davidson, Toronto, October 2019

Remarks at memorial for Graeme Gibson, at Art Gallery of Ontario

by Rick Salutin

I had the privilege of having lunch with Graeme regularly, every two or three weeks, during the last year or so. You don’t often get that opportunity with a friend, when the end is clearly in sight and you both know it and your conversations are predicated on that. That didn’t make the conversations morbid, they were full of awareness and perspective. That was down to Graeme’s total openness. From the start, he’d tell you that he had dementia. If he forgot a name, for instance. He may sometimes have not been clear on who I was but it didn’t matter. He knew we were friends and had a lot to talk about.

I’d like to offer a sense of the human being I spent that time with.

He talked most often about a single moment in his life: when his dad, Canada’s youngest brigadier-general, went off to World War Two in Europe and told Graeme, who was five or six, that it was now his responsibility to look after his mother and younger brother. ‘And I did,’ he’d always say with wonder and pride. It seemed to lay the basis for confidence in his own capacities, for the rest of his life, and he felt he owed it to his dad.

He was in the army himself for awhile, he said he was good at it, he was being trained as a sniper. But he decided not to stay since there wasn’t a war on the horizon as clearly necessary as that one had been. So he left. He tried university but didn’t like it, and turned to writing, which somehow seemed an obvious alternative to war. That was a time when writing as a craft or profession hadn’t yet been absorbed- to the degree it now has- into the universities. His contribution wasn’t just his own writing, it was pulling together the literary culture of the country in organizational form, via the Writers’ Union and Writers’ Trust. He was a natural born organizer- I say that admiringly, as someone who spent a fair amount of time working in the labour movement.

He said he never felt he was a pure writer- the way Peggy or Alice Munro were. He wrote what he felt he had in him and felt happy to leave it at that. He seemed proud to have done a number of different things in his life, starting with the army, including his relationship to birds and nature, and to contribute what he felt was in him to offer, then move on.

When we talked about politics and the future, he said, in his buoyant way, that he felt certain our species wasn’t going to make it. On the other hand, he hoped we would, since no one actually knows what’s going to happen and he’d made his own many efforts in the direction of a good outcome.

Jess asked me to say something about how he lived his life. He lived originally and eccentrically. It’s also how he thought. He had the most original turn of mind I’ve ever encountered. The things that came out of his mouth weren’t so much shocking as wholly unexpected. To the point that I have difficulty recalling examples if I’m asked for some. My son Gideon, who’d known Graeme since he was two years old, reminded me of one. We were visiting during the period when Stephen Harper turned on Mike Duffy, who Harper had appointed to the Senate. Duffy was taking fire from all sides. He and I had been at odds publicly for years but it never got personally unpleasant because whenever we crossed paths it was always at restaurants or celebratory events and Duffy was one of those people who’d never let anything interfere with a good meal. When he fell out with Harper, we started exchanging warm messages. It surprised me.

I asked them, What happened to the other Duffy I knew- that hostile, servile guy? Where did he go? Graeme, who was making tea, said, “He ate ’im.” I’m almost surprised at your laughter, clearly you got it. But it’s the kind of thing that stops you cold and takes a moment to catch up to. It’s so totally unexpected. Who else would say that? No one.

I often felt our lunches at the Gatto Nero on College could go on and on, and we’d close the place as we sometimes did in the past. When we were travelling in Scotland, for instance, and going from pub to pub on Skye or Lewis or Harris, sampling each place’s single malt. But our talks always ended after a couple of hours with Graeme saying he thought Peggy would be back by now. It was like an internal alarm clock had gone off. She was his anchor, especially in those wonderfully extended final years, including an amazing series of trips they took in the final phase, to Australia, where his mother’s family were, and Iceland, and the UK. He’d always think about her and want to get back. He could’ve just drawn a sketch of an anchor on a napkin and held it up.

I’m grateful for this chance. It’s been like prolonging our lunches. Thanks very much.

A TOAST – Carlyn Moulton

For the past several weeks, I’m sure each of us has been privately revisiting our own relationship with Graeme. Whether as friend or neighbour, uncle, in law, son or daughter or mate, we have been turning those memories over and over between our fingers, polishing them out of sight, private moments of grief and remembrance.

We will miss the way that only Graeme could say our individual names, When he said Matt or Grae, or Jess or Peggy, there was love in that voice. And when he said Matt or Grae or Jess or Peggy just so, with a slight question mark and a note of caution, it was a safe line he drew when he needed to remind us of our better selves, the perils of things better left unsaid or undone.

It was one of his most endearing characteristics that he treasured our flaws, the cracks in each of us that render us vulnerable. He told stories about all of you behind your backs, and they weren’t about the award you had won, the accolades you had received. He told the stories of our failings, with great empathy.I once managed to almost lose his young daughter to a death by drowning, when she was swept out to sea under my watch. Other parents might have had harsher words, but Graeme allowed that it must have been terrifying for me, and poured me a drink.

He didn’t often give advice, but when he did, it was worth remembering. When I was in my twenties, he told me that unpredictability could be the greatest weapon or advantage, and I credit that advice with once saving my life.

And despite his reputation as a fine naturalist – or he might have argued, because of it – some of you may have shared stories of encounters with ghosts with Graeme, for there were a few which he insisted upon, chilly brushes with spectral figures that pushed by on the steps, that moved candlesticks in the night.

Yet In this particular moment, we stand reminded also of our collective relationship and knowledge of Graeme, our shared loss yes, but more, our shared luck.

Our luck to have known Graeme the Alchemist. A man who could take the simplest of tools – a pair of binoculars, a soup ladle, his voice, and make the ordinary and the every day something much more meaningful, by shifting our perspective, adding a bit more garlic, turning the journey into a ballad.

Our privilege to have known Graeme the humanist. A man who had faith in the virtue of a principled and persistent optimism, whose irrepressible and dark humour erupted so readily into that unmistakeable and booming laugh, making our fears smaller through his heightened sense of the absurd, reminding us again of why we go on, finding opportunities for kindness.

And it is our collective great fortune to be able to celebrate his legacy, for Graeme was a singularly gifted man, unfailingly generous, tender and nurturing in the sharing of his gifts, resolute and demanding of us that we find our own. He gave us a master class in a life well lived.

And so let us toast. To Graeme. May his spirit haunt us all till the end of our days.